Learning Theories Assignment

|

Learning theories that have been utilised in an informal education organisation |

||

| NameStudent Number

Course Module |

Hugh McLainD13124350

MSc in Applied eLearning (DT580) Learning Theories |

|

Introduction

In this paper I explore a selection of learning theories and critically discuss how I have applied them in an authentic real life situation in which I am involved in an educator role. While my current professional practice in the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine’s Staff Training and Development Unit can directly benefit from this learning theory exploration, the context of the paper is as an adult leader for over 20 years in the Irish Scout Movement; practical examples will be drawn from this non-formal education context, but lessons learnt are applicable to my professional role also.

The World Organization of the Scout Movement (WOSM) is an independent, worldwide, non-profit and non-partisan organisation which serves the Scout Movement. Its purpose is to promote unity and the understanding of Scouting’s purpose and principles, while facilitating its expansion and development (WOSM, 1998, p.5). Scouting Ireland is registered as the national Scouting Association for Ireland with the WOSM. Scouting is a non-formal educational movement so in other words, it is not part of the formal school educational system, nor is it informal (friends, media, etc.) as it does offer a structured approach to education.

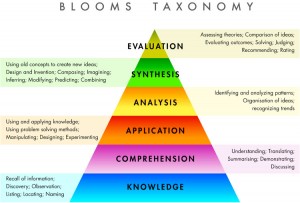

The following sections of the paper concentrate specifically on Behaviourism and Cognitivism, and how they can be used in conjunction with each other to help achieve the required goals of my leadership role in my local Scout Troop. Blooms taxonomy can be utilised in this context to show how youth members gain knowledge, comprehend it and then apply it to scouting practice. The paper will then discuss how a transition can occur from behaviourist to cognitivist principles, depending on the individual scout’s age and ability.

Finally, the paper will investigate Knowles’ work on pedagogy versus andragogy, and the identification of six principles of the adult learner; specifically an explanation will be presented around my beliefs on how the principles of andragogy can be applied to children in this non-formal learning context, as well as adults. There is disagreement in the literature about andragogy only applying to adults, Smith (2010) states the age and amount of experience makes no educational difference. The main problem is the definition of an adult and how experience can be used; I believe that young people’s experiences are not any less real or less rich than those of adults. I will argue that these principles can also be applied to adolescent children as well.

How Behaviourism is manifested in Scouting

Jordan et al. (2008) state that Behaviourism is a theory of learning which concentrates on behavioural changes in organisms. There are many theories on how to change an individual’s behaviours, which include Pavlov’s classical conditioning, Thorndike’s law of effect, Skinner’s operative conditioning, and Bandura’s observational behaviour to name a few. In the Scout Troop context, classical conditioning is engaged to maintain discipline among the scouts with a command (either oral or whistle), being given with an associated hand gesture when quiet is required. After a time, the hand gesture can be utilised without the associated command as the Scouts will realise via the hand gesture that quietness is required and generally they all comply. Sometimes however the signal could be missed if there is much noise or mixed activity occurring such as a game being played. I have found in any noisy environment that a whistle will always be heard and I make use of it to reinforce the hand gesture.

The law of effects are utilised with specific scouting actions being rewarded, such as good attendance and wearing correct uniform. This demonstrates to the Scouts that their actions have consequences, and failure to abide by the agreed set of rules will result in a form of ‘punishment’. This is linked closely to operant conditioning which is used to positively or negatively reinforce scouting behaviour. Awards such as ‘Scout of the month’ and ‘Patrol of the year’ both have positive and negative ramifications and encourage good behaviour whilst punishing undesirable behaviour. Punishment would be in the form of loss of rewards or privileges such as losing out on playing a final game during an evening meeting if order is not maintained or not having as much free-time on camp. However in a group situation, if even one Scout decides not to follow the rules, then all could be affected; this can lead onto all of them losing faith in the rewards system or some being indirectly punished even though they followed the agreed rules.

Observational behaviour is very important in Scouting which employs a ‘lead by example’ system. Yaffe and Kark (2011) defined a role model as a cognitive construction based on the attributes of people in social roles to which an individual desires to increase similarity by emulating those attributes and each group member may identify with various role models inside and outside the organization. All Scouts observe the behaviour of adult Scouters and younger Scouts observe the behaviour of their older peers. If someone in a position of authority, i.e. an adult scouter or youth Patrol Leader acts in a particular manner, then it is implied that this behaviour is acceptable. This means that everyone needs to be conscious of how they act; we need to ensure that the right people are selected for a leadership position for the right reasons. It is important however to ensure that new ideas are embraced to keep the whole experience fresh.

I found it useful to engage with Bloom’s Taxonomy for my thinking on this module (see Figure I below), and see the link between Behaviourism and the Knowledge Layer as it help new Scouts to discover new information by listening and recalling it later. For example when they see a tent for the first time they need to be presented with the major part, such as poles – pegs – flysheet, and this is done by them observing someone laying them out and listening. Once they have discovered this new information they can see how it all fits together.

While behaviourism is an important learning theory for Scouting Leadership, as it can help reinforce certain behaviours in the young scouts, it can also be seen as manipulative and WOSM would argue that it does not fully allow the learners to develop themselves ( 2005, p.32). While I concur with this perspective, I try to remember that everyone learns new knowledge differently and our scout training needs to take account of this.

Cognitivism and how information is processed in a Scouting Context

Cognitivism provides a way to explore the mental processes of learning, specifically by taking previous blocks of knowledge and linking them together in different schemata to create the bigger picture. Carlile & Jordan (2005) use an example from computer scientists in the 1950’s looking at the input–process–output model, with processing being the cognitive element. A look at the cognitivist paradigm on Learning-Theories.com reveals that the “black box” of the mind should be opened and understood, where the learner is viewed as an information processor (like a computer).

When dealing with the Patrol Leaders and Adult Scouters, a cognitive approach is suitable, as it would be assumed that they have some prior knowledge they can call on to complete a task and process the important information. They comprehend the new knowledge and use it to achieve results, which can be related to layers two and three in Bloom’s Taxonomy (see Figure I above). For example when tying a knot, prior knowledge about terminology, equipment required and use of knots can be linked to learning how to construct a new knot. The new information being presented is the name of the new knot, steps to tie it and its function. Existing schema can be adapted to help learn the new knot, for example after you have tied your first knot you will know about purpose, function and equipment required. We can use a schema (See Appendix 1) to help us remember how this knot is tied that shows its purpose, function and equipment required. A slight alteration to the content and we can now tie a different knot.

Cognitivism involves encoding knowledge to long-term memory to provide a deep rather than surface form of learning. Sweller’s (1998) Cognitive Load Theory argues that learners will be more effective in retaining information in long term memory for recall when required, so as not to overload the working memory. He presented three types of cognitive load: intrinsic cognitive load deals with the inherent level of difficulty associated with a specific instructional topic; germane cognitive load deals with the processing, construction and automation of schemas; extraneous cognitive load deals with the manner in which information is presented to learners. Designers need to decrease extraneous cognitive load during learning, and refocus learner’s attention toward germane materials.

The distinction between a deep approach to learning, through which the student seeks personal understanding, and a surface approach, where the student is content to reproduce the information presented during the course, is in how the learner organises the new knowledge. Cognitive learners want to understand the information they are receiving and need to be able to comprehend, apply, analyse, synthesis and evaluate knowledge to reinforce it into their long term memory. It is not enough just to regurgitate the information.

Schemata can be used to organise relevant concepts into logical flows. Bartlett’s (1932) seminal book laid the foundations for his later schema theory (cited in Carbon & Albrecht, 2012). These schemata can be flexible and be top-down or bottom-up in their approach. Scouts utilise schema, or a series of steps, to complete a task from simply tying a knot to building a 20-foot pioneering structure. Each specific task has a series of steps that can be followed to ensure it is completed (see Appendix 1 for Knot examples). I have found step-by-step instruction to be very useful when teaching the Scouts in my troop; however there have been instances where a younger member of the Troop cannot remember the sequence of steps. Another learning approach, drawing on behaviourist principles, could be used in these cases, as not everyone can relate to schemas.

Andragogy is not just for adults

Pedagogy, from the latin paid meaning child and agogos meaning leading (Smith, 2010), is a method and practice of teaching especially to teach children. Malcolm Knowles, an American practitioner and theorist of adult education, defined andragogy, from the latin andr meaning man and agogos meaning leading (Smith, 2010), as “the art and science of helping adults learn” (Knowles et al., 2005,p.61). He identified six principles of adult learning as: (1) the learner’s need to know, (2) self-concept of the learner, (3) prior experience of the learner, (4) readiness to learn, (5) orientation to learning, and (6) motivation to learn.

Through my extensive experience in Scouting, I believe that these principles can also be applied to older Scouts, approximately 13 years and older, and not just adult learners. Literature is showing a shift away from these principles only applying to adult learning contexts and arguing that they can be applied in instructional situations involving children. A major problem is the definition of an adult learner, with Holmes & Abington-Cooper (2000) concluding that there is no agreement in the literature as to what constitutes an adult learner. They state age is a characteristic and not an identifier and other characteristic have to be used. Pappas (2013) states adults are characterised by maturity, self-confidence, autonomy, solid decision-making, and are generally more practical, multi-tasking, purposeful, self-directed, experienced, and less open-minded and receptive to change. All these traits affect their motivation, as well as their ability to learn. I believe that these traits can also apply to the older Scout.

While I acknowledge that Scouting is a non-formal educational association whereas Knowles’ theories are based on formal education contexts, I believe that the principles can be applied in both areas. I believe that if any learner is motivated and engages in their learning, all but one of the six principles outlined above can apply to them; I offer that life experiences is the only one that does not directly transfer over to children. Whitby (2013) describes his experiences as a retired educator and reflects on how andragogical principles should also be applied to children. He states that ‘relevance’ is important to the adult learner but argues it is also important to the child learner also. Smith (2010) also argues that children’s and young people’s experiences are as important as those of an adult who has had greater time to accumulate them, more time does not necessarily mean better quality experiences.

A Scout that has been there for a year or two could quite easily acquire more knowledge and experience that an adult that has never been involved in Scouting, examples of this would be in areas such as campcraft, tent pitching, navigation and rope work. In my experience as a Scouter, it is the children who really want to be there who engage the most; those children sent by parent because Scouting will be good for them will not engage and become bored which eventually leads to discipline issues.

Conclusion

I have aimed in this paper to establish that in my personal experience in leading a Scout Troop that no one learning theory can be used in isolation. All the approaches to learning discussed in the paper have merit for my context and can be blended for maximum effect. I have discussed how behaviourism is used for younger scouts to instil the basic principles but as they get older, how cognitivism can be utilised to help individuals gain more knowledge of scouting activities and principles.

I also found it helpful to look at Knowles’ work on Andragogy and have argued that the principles of andragogy can also apply to older children who wish to engage in their learning. There has been a shift in the literature towards this point of view with the main point of controversy around defining what an adult learner is (Smith 2010 – Holmes & Abington-Cooper 2000). Whilst age is normally used to define an adult it is not a good indicator to use in isolation when looking at learners as maturity, self-confidence, autonomy and experience need to be examined also.

I have found that I can carry this understanding of learning theories and resultant experiences into my professional practice for the future – how I design training courses will change now as I will try to ensure new information is presented to learners in a manner that allows all to absorb it. At present the existing training courses have been deliver in a very pedagogical manner, to adults, with the content and delivery mode being specified with no user interaction. Although sometimes, such as induction courses, this will need to be the case there are also courses that could be redesigned with the help of those that have done the course. For example the management development courses could be tailored to specific manager, i.e. junior, middle and senior, and delivered to the relevant staff.

This understanding can be extended into how I deliver training, as I have a better appreciation of how people learn and that there are different types out there. Delivery, where appropriate, will have to be tailored to ensure maximum benefit for the learner. At present the majority of training is done either in classroom or workshop format and this is being extended to an elearning environment. Understanding of these principles will be essential as the course content needs to be correct for the potential learners.

References

Carbon C.C., & Albrecht S. (2012). Bartlett’s schema theory: The unreplicated “portrait d’homme” series from 1932. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 65 (11), 2258–2270.

Carlile, O., & Jordan, A. (2005). It Works in Practice but will it Work in Theory? The Theoretical Underpinnings of Pedagogy, AISHE Readings. Retrieved October 1, 2013 from http://www.aishe.org/readings/2005-1/carlile-jordan-IT_WORKS_IN_PRACTICE_BUT_WILL_IT_WORK_IN_THEORY.html

Holmes G. and Abington-Cooper M. (2000), Pedagogy vs. Andragogy: A False Dichotomy, The Journal of Technological Studies, Volume 26, Number 2, http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/ejournals/JOTS/Summer-Fall-2000/holmes.html, Retrieved 18 December 2013

Jordan, A., Carlile, O., & Stack, O. (2008). Approaches to learning for teachers. Berkshire: Open University Press.

Knowles, M., Holton, E.F., & Swanson, R.A. (2005). The Adult Learner. (Sixth Edition), Oxford: Elsivere..

Learning-Theories.com – Cognitivism, http://www.learning-theories.com/cognitivism.html, accessed 1 October 2013.

NCCA website, Towards a Framework for Junior Cycle. Retrieved October 24, 2013 from http://ncca.ie/framework/home.htm

Pappas, C. (2013), 8 Important Characteristics of Adult Learners, Published in Concepts Wednesday, 08 May 2013, http://elearningindustry.com/8-important-characteristics-of-adult-learners, retrieved 19 December 2013.

Smith M. K. (2010), ‘Andragogy’, the encyclopaedia of informal Education, http://infed.org/mobi/andragogy-what-is-it-and-does-it-help-thinking-about-adult-learning, Retrieved 18 December 2013

Sweller, J., Van Merrienboer J.J.V., & Paas F.G.W.C. (1998). Cognitive Architecture and Instructional Design. Educational Psychology Review, 10 (3), INSERT PAGE NUMBERS.

Whitby T. (2013) Pedagogy vs. Andragogy. Retrieved October 22, 2013 from http://networkedblogs.com/KTGoI

WOSM (World Organization of the Scout Movement) (1998). Scouting: An Educational System. Geneva: World Scout Bureau.

WOSM (World Organization of the Scout Movement) (2005). World Adult Resources Handbook. Geneva: World Scout Bureau.

Yaffe, T., & Kark, R. (2011), Leading by example: The case of leader OCB. Journal of Applied Psychology, Volume 96 Issue 4, Pg:806-826.

Appendix I

Tying a knot

Below are two schema for tying knots: reef and figure of eight. The equipment needed for both is as stated. The function of each knot is stated under the list of steps. A practical demonstration is also needed to learn these knots.

Knowledge of some terminology is required, i.e. ‘what is the bite’ and ‘what is the tail end’ of a rope.

Reef Knot

Material required: two pieces of rope.

- Left over right

- Top one under

- Right over left

- Bottom one over

- Pull together until both ends bite

Purpose: To tie ropes of equal thickness together.

Figure of eight

Material required: one piece of long rope.

- Make a loop

- Wrap the tail around the loop

- Put tail through loop from front and pull until it bites

Function: Can be used as a stopper knot or to tie off on a harness.

Above are two schemata that helps the learner to tie two different knots, however they are structured the same, i.e. shows material required – steps to take – function of knot, but the content is different. Gaining knowledge to tie the first knot, including information and terminology, can give a learner the building blocks to tie other knots. The first schema can be replaced with the second one.